The Delaware, Lackawanna & Western Railroad Company

The Delaware, Lackawanna and Western Railroad (better known as the Lackawanna and not to be confused with current shortline, Delaware-Lackawanna) was another of the Northeast’s many anthracite carriers with a history tracing back to the early 19th century. During the company’s height it never reached 1,000 miles but was nevertheless a well-managed system throughout its history enabling it to avoid bankruptcy from the time of its formation in the early 1850s until its merger with the Erie more than a century later.

**********

RICHFIELD SPRINGS BRANCH

The Richfield Springs branch of the The Delaware, Lackawanna & Western Railroad Company extended through Bridgewater, where it connected with the Unadilla Valley Railroad, a shortline that served Edmeston and New Berlin to Richfield Springs on Canadarago Lake, once a rather fashionable resort. Here, from 1905 until 1940, the DL&W had a passenger and freight connection with the Southern New York Railway, an interurban to Oneonta. Milk and light freight were the chief sources of revenue on this branch. Delaware Otsego subsidiary Central New York Railroad acquired this branch from Richfield Jct. to Richfield Springs, 22 miles, in 1973. Enginehouse was at Richfield Springs. Became part of NYS&W northern division after NYS&W bought the DL&W Syracuse & Utica branches from Conrail in 1982. Traffic on line gradually dropped off. Line east from Bridgewater embargoed in 1990. Abandoned and track removed in 1995, westerly 2-3 miles left in place for stone trains. In 2009: This old railroad is now owned by the Utica, Chenango and Susquehanna Valley LLC in Richfield Springs. They also own the 1930 Newark Milk and Cream Company creamery in South Columbia.

**********

ITHACA BRANCH

In earlier articles I have written about the Lackawanna, mention is made of the 34-mile former branch to Ithaca. Not only was it significant historically, but it was also a very interesting operationally. It ran between Owego on the DL&W main line and the college town of Ithaca on Cayuga Lake.

It was the second oldest railroad in the state and was constructed in 1833-34 by the Ithaca and Owego Railroad. This road had originally been chartered in 1828. In 1843 the Cayuga & Susquehanna Railroad acquired it through a mortgage foreclosure. In 1855 it was leased to the Lackawanna but did not become officially owned by the DL&W until July 23, 1946.

Into the 1920’s Ithaca was busy with several passenger trains pulled by 4-4-0 camelbacks, a daily freight, and a yard switcher which doubled as a pusher on the switchback leading out of Ithaca. There were even automatic block semaphore signals. Passenger service ended in 1942 and steam gave way to diesels in 1951. Passenger service was more popular on the Lehigh Valley (which also served Ithaca) because of the direct Pennsylvania Station connection in New York City. Until 1933 there was a New York sleeper serving Ithaca. It arrived at 7:30am and left at 11:05pm. When passenger service ceased, there were two scheduled passenger runs left (12:20pm and 6:00pm arrivals/9:30am and 1:25pm departures). In addition, student specials ran to Cornell University.

A trip over the branch featured a long bridge over the Susquehanna River leaving Owego. Intermediate stops were at Catatonk (5.4 miles from Owego); Candor (10.7 miles from Owego); and Willseyville (16 miles from Owego and 18 from Ithaca). The real feature of the ride began on the approach to Ithaca. At that point, the line was about 500 feet above the city. Originally, an inclined plane had been used, but it had been replaced by a switchback in 1850. There was a sensational view of the city and the lake. The track between the upper and lower switches of the switchback was 1.1 miles with a gradient of 100 feet per mile. It took five and a half miles to cover what a crow did in one and a half miles. One street crossed the line three times.

The end of passenger service was the beginning of the end of the branch. Signals were removed and there was no longer a switcher in Ithaca. LCL business remained only at Ithaca and Candor. The track between Ithaca and Candor was abandoned in 1956 and the Owego-Candor section in 1957. The branch was in bad condition as no maintenance had been done since passenger trains quit and the bridge at Owego needed heavy repairs.

The Lehigh Valley bought the trackage in Ithaca and operated it as an industrial siding.

Ithaca Branch

Originally, Ithaca & Owego, later Cayuga & Susquehanna.

| Station | Mile | Note |

| Ithaca | 0 | |

| Lower Switch | 4.51 | Switchback, originally incline plane up South Hill. |

| Upper Switch | 5.62 | as above |

| Conover | 5.82 | |

| Summit | 9.73 | |

| Caroline | 12.24 | |

| Wilseyville | 18.06 | |

| Candor | 23.37 | |

| Catatonk | 28.70 | |

| Owego | 34.03 |

Abandonments:

Passenger service discontinued March 29, 1942

Abandonment authorized Oct. 25, 1956

Discontinued Ithaca-Candor, Dec. 4, 1956;

Candor to Oswego, May 25, 1957.

Bridge over Susquehanna River in Owego River removed in 1959.

Last locomotive on line: #409, Alco #69257 600 HP switcher. Became Erie-Lackawanna #325.

**********

DL&W & Erie on the West Side of New York City

Pier 68 alongside the West Side Highway was a Lackawanna freight terminal. Both the pier and the highway deterioriated and both are gone. The Lackawanna had no connection with the West Side Freight Railroad.

**********

OSWEGO AND SYRACUSE RAILROAD

This Company was formed April 29, 1839, and the route was surveyed during the summer of that year. The Company was fully organized March 25, 1847. The road was opened in October, 1848, thirty-five miles and a half in length. In 1872 it passed under the management of the Delaware, Lackawanna and Western Railroad Company. It finally merged with the DL&W in 1945.

DL&W in Oswego

The Lackawanna had a coal dock in Oswego, but it was older and not too large. Many Great Lakes boats were too long and too deep for loading at the Oswego dock. Lots of times, coal loads had to go to the Pennsylvania for loading at Sodus Point. The matter of extra dredging at Oswego was up but the Railroad did not seem disposed to spend the extra money to dredge to a sufficient depth and length to accommodate the modern boats.

**********

The Utica, Chenango & Susquehanna Valley Railroad was organized in 1866 and came under the Lackawanna in 1870. Inclusion of the Greene Railroad Company linked up this road with the Syracuse route at Chenango Forks. As well as providing an important link, it also put the Lackawanna in the resort business. The branch to Richfield Springs was on Canadarago Lake and tourist trains now ran from Hoboken. The Utica-Binghamton line was a big dairy carrier and solid milk trains ran until the late 1940’s. Army reservists also used this line up to the 50’s to travel from New Jersey to Utica then over the New York Central’s St. Lawrence Division to Camp Drum near Watertown.

Scranton Division, Utica Branch |

| Station | Mile | Note |

| Chenango Forks | 11.1 | |

| Willard’s | 12.0 | |

| Greene | 19.2 | |

| Brisben | 25.0 | |

| Coventry | 28.5 | |

| Oxford | 33.1 | |

| Haynes | 36.5 | |

| Norwich | 41.3 | Ontario & Western |

| Galena | 46.9 | |

| Sherburne | 52.4 | |

| Earlville | 57.5 | |

| Poolville | 60.0 | |

| Hubbardsville | 64.2 | |

| North Brookfield | 68.0 | |

| Sangerfield | 72.4 | |

| Waterville | 73.7 | |

| Paris | 77.9 | |

| Richfield Junction | 81.7 | Richfield Springs Branch |

| Clayville | 83.9 | |

| Sauquoit | 85.9 | |

| Chadwicks | 87.3 | |

| Washington Mills | 89.9 | |

| New Hartford | 91.1 | |

| West Utica | 94.0 | |

| Utica | 95.2 | NYC Union Station |

Richfield Springs Branch

Station |

Mile |

Note |

Richfield Junction |

0 |

|

Bridgewater |

4.7 |

Unadilla Valley Railroad |

Unadilla Forks |

5.5 |

|

West Winfield |

7.6 |

|

East Winfield |

9.7 |

| Cedarvale | 11.6 | |

| Miller’s Mills | 13.2 | |

| Young’s Crossing | 14.0 | |

| South Columbia | 18.0 | |

| Richfield Springs | 21.7 |

Abandonments:

Passenger service discontinued April 29, 1950.

Utica branch to Conrail, April 1, 1976, to New York, Susquehanna & Western, April, 1982.

Milk train, which carried passengers on Richfield Springs branch, discontinued July, 1938.

NYS&W operated this branch as “Central New York RR.” Abandoned Bridgewater to Richfield Springs in 1995.

**********

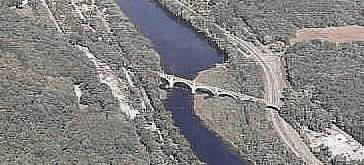

Starucca Viaduct

IN NORTHERN PENNSYLVANIA IS ONE OF THE WORLD’S WONDERS

The view up the Susquehanna River valley is one of surpassing beauty. It has been an inspiration to painter and poet alike through the years. The Starrucca Viaduct stands as a monument to the instinctive artistry of its builders. Constructed of native stone it nestles in the Starrucca Valley between the foothills of the Blue Ridge and Catskill Mountains; and looks as if it belongs.

This structure is a historic landmark bridge, 1040 feet long, comprised of 17 Roman arches and constructed of blocks of cut sandstone. Begun in 1847, it was completed in record time in November, 1848. It is in active use today, over which many trains run on a regular, daily basis.

The building of the Starrucca Viaduct and the history of the building of the Erie Railroad in this vicinity has been an interesting one.

Beginning in 1831, Governor Marcy appointed James Seymour to survey a rail route in southern New York and through Pennsylvania. The surveying parties, trying to locate a way for the railroad, found the nine miles from Gulf Summit PA to Susquehanna PA, most forbidding. The obstacles of nature appeared insurmountable to everyone.

Various routes were tried and given up. In 1840 a survey party discovered the remarkable glen at Gulf Summit, between the waters of the Cascade Creek, going to the Susquehanna, and McClure Brook, going to the Delaware. An engineer named John Anderson traced a line from Deposit NY to Lanesboro PA passing through the rocks and just wide enough for the road. Finding a way through this rocky glen enabled them to get over on the Susquehanna River side, which would allow them a good grade to Elmira and west. The grade of this route was 66 feet on the Delaware side and 70 feet on the Susquehanna side, a distance of 16 miles.

The 1834 survey was also unsatisfactory in that the line missed Binghamton. The 1840 survey passed directly through the village. Legislation was passed and it was decided to overcome the obstacles of nature and build the road over the Randolph hills to Susquehanna. This was the most difficult and expensive nine miles of railroad ever built up to that time. A monument still stands in Deposit where ground was broken for the line.

The cost to carve a roadbed (wide enough for one track) through the glen of rocks at Gulf Summit was the then-enormous sum of $200,000. A strong current of air was constantly sweeping through it, and the temperature on the hottest days was uncomfortably cool. Winter snow blockages resulted whenever a wintry storm swept over the mountain. The cut ended up 150 feet deep.

Nearby a gulf 184 feet deep and 250 feet wide over the Cascade Creek had to be bridged. Three miles beyond, at Lanesboro, a bridge over the Starrucca Creek was needed. This proved to be especially difficult as the distance was over a quarter of a mile and more than 110 feet deep. The Canawacta Creek valley at the lower end of Lanesboro also required bridging.

The first contract for building the Starrucca viaduct was let in 1847 for $375,000. The builders went belly up. Two other contractors failed. A proposition was submitted to James P. Kirkwood, a Scotchman. He visited the site and carefully investigated it before telling the Erie he could do it provided cost was no object. He got the go-ahead.

Three miles up the Starrucca Creek he opened quarries to get the stone. Next he constructed a wooden track on each side of the stream which brought the material to the work in cars. Stone was also brought from a quarry near Cascade. A city of tents arose to house the 800 workers he hired. A half million feet of lumber was used in the false work which was extended across the valley. Operations were conducted both day and night and the viaduct was completed ahead of schedule. Laborers received a wage of $1.00 a day.

The historic bridge appears to be everlasting and proved the Erie motto “Old Reliable”. It even outlasted the Erie! Sometimes called the “Stone Bridge”, it stands today as a monument to the engineering science and stone masons of that day.

Some statistics on the viaduct:

Built to accommodate only one track (broad gauge) and the 1848 engines of 100,000 pounds, it has long carried two tracks and engines of over 800,000 pounds. Only lime and sand mortar were used in building the bridge. The more weight running over it, the more compact and solid it becomes. Every pier stands today just as it did when completed, and the gigantic top stones on top of the bridge are a tribute to the skill of the builders.

After completing the bridge, there was another worthwhile spectacle in the job of removing the falsework. It had to be done in the winter because of the danger of fire which would have ruined the whole bridge. Men were suspended 100 feet above the valley prying out beams and timbers and lowering them to the ground.

Brawls were quite common outside of working hours, as would be expected of any army composed of so many nationalities. Remarkably, no man was killed or injured until the removal of the temporary false work when one man was injured. It is thought he died afterwards.

The first engine to cross the viaduct was named “Orange”. Nobody dared ride it so everybody got off. They gave it enough steam to keep it moving. Men reboarded it on the other side.

Also in northeastern Pennsylvania is the Tunkhannock Viaduct. Inspired by, and modeled after, the incredible ancient Roman aqueduct at what is today Nimes, France, this viaduct is a magnificent, landmark structure which helped propel American engineering skills into a world class. This railroad bridge was completed in 1915; is constructed entirely of formed concrete, displacing 4.5 million cubic feet; is 2,375 feet long and stands 240 feet high.

**********

Once upon a time, milk trains were important

There were two basic types of milk trains – the very slow all-stops local that picked up milk cans from rural platforms and delivered them to a local creamery, and those that moved consolidated carloads from these creameries to big city bottling plants. Individual cars sometimes moved on lesser trains. These were dedicated trains of purpose-built cars carrying milk. Early on, all milk was shipped in cans, which lead to specialized “can cars” with larger side doors to facilitate loading and unloading (some roads just used baggage cars). In later years, bulk carriers with glass-lined tanks were used. Speed was the key to preventing spoilage, so milk cars were set up for high speed service, featuring the same types of trucks, brakes, communication & steam lines as found on passenger cars.

REFERENCE |

| List of New York Railroads List of Pennsylvania Railroads |

| Delaware, Lackawanna and Western Railroad |

| Anthracite Railroads Historical Society, Inc. |

| DL&W Utica Division |

| Gerald’s Railroads of New Jersey |

| The Lackawanna Trail |

| Lackawanna Steam Locomotives |

| Hoboken’s Lackawanna Terminal |

| Northeastern Pennsylvania Rail and Anthracite Page |

| The NJ Transit WebSite |

| The Phoebe Snow The Lackawanna’s answer to mighty New York Central in the New York to Buffalo market. Later extended by successor Erie Lackawanna through to Chicago. Phoebe Snow – July 1954 |

**********

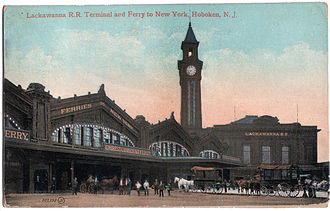

The Delaware, Lackawanna and Western Railroad’s Hoboken Terminal is the only active surviving railroad terminal alongside the Hudson River and is a nationally recognized historical site.

**********

Erie-Lackawanna Railroad

The Erie Railroad and the Delaware, Lackawanna & Western Railroad were merged on October 17, 1960. The new Erie-Lackawanna adopted the rectangular Lackawanna logo and added the Erie diamond. The result was an encircled broken “E” within a diamond. The hyphen later dropped in the name to become Erie Lackawanna. The black and yellow Erie paint scheme prevailed on locomotives at the merger, but within a few years, the old Lackawanna colors – maroon, yellow and grey – returned.

The new railroad was a 3031-mile route between Chicago, Cleveland, Buffalo and New York. Merger talks had begun in 1956. William White, Delaware & Hudson president in 1956 had worked for the Erie for 25 years. Original discussions had included the D&H. In 1955, Hurricane Diane had put the DL&W out of business for 29 days. There were other problems with the railroads – for instance, commuters. The DL&W used to be profitable but the Erie had numerous bankruptcies over the years. In 1959, D&H got out of the merger picture. Following the recent history of its parents, Erie Lackawanna had a lifetime of deficit operation except 1965 and 1966.

Other actions had been taken before 1960. The Erie had shifted its terminal from Jersey City to Hoboken in 1956.

The merger was opposed by railroads operating into Buffalo because a combined Erie and Lackawanna could bypass them. One road was the Nickel Plate. NKP had once controlled 54% of Erie but lost it in 1930’s. DL&W had held 15% of NKP but sold in 1959. Seeing formerly friendly connections drying up, it opposed the merger. The merger saw 2199 miles of Erie plus 918 miles of DL&W less 86 miles abandoned equalling 3031 miles. The new road was organized into two districts – the western was all-Erie while the eastern a mix. “Friendly Service Route” was slogan for the new road. It had 31,747 freight cars, 1,158 passenger cars, 695 diesels, 20,000 employees. Erie was the “surviving” entity in merger and the new headquarters was located in Cleveland. The new road had a series of leaders until William White took over in 1963. Before D&H, he had been New York Central president until Robert Young won his famous proxy battle in 1953.

Both roads were a combination of numerous once-independent lines. In the 1940’s, the DL&W had acquired, either by purchase of stock or merger, all 18 of its leased lines. Similar action had occurred on the Erie.

The Delaware Division of the Erie became the Delaware Subdivision of the Susquehanna Division. Over a century old, Port Jervis to Susquehanna, Pennsylvania was opened by 1848. Construction had begun in 1835 near Deposit but was held up by financial problems. A New York City fire and a national business panic bankrupt many supporters. The fact that much construction was on low trestlework rather than on the ground made construction expensive.

A famous point on the Erie route was Gulf Summit. It was 1373 feet high. Pusher locomotives were used until 1963. Erie used Mallet Triplex 2-8-8-8-2’s built in 1914. Also used was the “Matt H. Shay”. The route included Starucca Viaduct and the old station-hotel at Susquehanna. Built in 1865, it was 3 stories high and had also served as the old division office. The former Erie R.R. car shops were located here. The Delaware & Hudson Penn Division between Nineveh, NY and Wilkes-Barre ran under the Starucca Viaduct. There was a connection between the two roads at Jefferson Junction.

The NY & Erie was granted its charter in 1832. It was intended to be a New York State-only road to connect Dunkirk on Lake Erie with the eastern portion of the state and to bolster the Southern Tier which had been hurt economically by the Erie Canal. The whole road from Piermont to Dunkirk opened in 1851. Originally it had been 6-foot guage. The original charter had specified a railhead at Piermont-on-Hudson. There was a 19 mile branch Greycourt to Newburgh. The New York & Erie reached Jersey City by 1861 (Pavonia Terminal). Two early New Jersey roads connected with the Erie at Suffern and eventually were leased by the Erie and finally becoming the main line. Other roads into Jersey City fell under the Erie as time went on. One was the New Jersey & New York to Nanuet and Haverstraw (42 miles). Another was the Pascack Valley Line to Spring Valley. New York & Greenwood Lake and the Bergen County Railroad were added as well as the Northern Railroad of NJ from Nyack.

In 1874 the Erie expanded westward from Salamanaca to Dayton, OH by leasing the Atlantic and Great Western. In 1880, the six-foot guage finally went standard. About this time, Erie got its Chicago access as well as a line to Cincinnati. The Erie also reached Indianapolis and Cleveland by the acquisition route. The Erie had always been eyed by other railroads. James Hill, E.H. Harriman and the Van Sweringen brothers were all stockholders at one time. Erie never electrified its New York commuter operations but did so to its branch between Rochester and Mt. Morris. Erie owned the New York, Susquehanna & Western and the Bath & Hammondsport but lost both.

1909 saw construction of the 43 mile Graham cutoff. Running from Newburgh Junction, it passed under Moodna Viaduct and through Campbell Hall (Maybrook). It rejoins the main at Howells Junction. The Graham cutoff was good for freight as it had low grades.

The Lackawanna began with the Cayuga & Susquehanna in 1834 between Cayuga and Ithaca then with the Morris & Essex in 1836. 1849 marked the beginning of the parent Delaware, Lackawanna & Western when the Liggetts’s Gap Railroad connected Scranton with the Erie at Great Bend, PA. This line consolidated in 1853 with the Delaware & Cobbs Gap which connected Scranton with the Delaware River. Very important was the Scranton Division of the DL&W. The headquarters here had offices and shops. This division included the Tunkhannock Viaduct which was 2375 feet long and 240 feet high. It was completed in 1915 as part of DL&W president William Truesdale’s improvement program. After the 1960 merger, most EL traffic used the old Erie.

DL&W had the shortest passenger route between New York and Buffalo. Erie’s was the longest. In 1960, passengers could reach Erie Lackawanna’s passenger terminal at Hoboken by bus from Rockefeller Center, ferry, or tube (now PATH). The lines famous PHOEBE SNOW left at 10:35 a.m. and arrived in Buffalo 7:15 p.m. Passenger service was eliminated 1970 and most equipment was scrapped. The observation cars went to the Long Island for Montauk service. Later they became business cars for Metro-North.

Some coaches went to the D&H. Four 62-seat lightweight coaches were acquired in September, 1970. Some of these were refurbished for “Adirondack” service and later were used by the New York MTA for Poughkeepsie service. A pair of ex-Erie heavyweight coaches were also used in the 1970’s.

Other Erie Lackawanna equipment went to the New York MTA and saw service on the New Haven. A string of these cars, still in EL markings, ran between Harrison and Grand Central behind FL-9’s.

White died in 1967. In 1968, Erie Lackawanna came under Dereco (A Norfolk & Western “arms length” subsidiary which also picked up D&H). The road went to CONRAIL in 1976. In 1972 Hurricane Agnes flooded 135 miles of the Erie Lackawanna. It caused millions of dollars in losses and brought bankruptcy. More damage was done when the Penn Central merger eliminated interchange at Maybrook. The Penn Central merger had certain conditions that were designed to protect Erie Lackawanna by maintaining trains over the New Haven via Maybrook. Erie Lackawanna claimed its service from Chicago to New England had been slowed by 22 hours. PC countered that EL trains were usually late and improperly blocked for fast addition to PC trains.

Erie had survived Jay Gould (a 19th Century Ivan Boesky) but couldn’t cope with changes in the economy

Built in 1907, Hoboken Terminal still serves. It has six ferry slips (now unused) as DL&W operated ferries to 23rd Street, Christopher Street and Barkley Street. It also connects with PATH trains. 18 tracks served both commuter and long distance traffic.

Lackawanna’s New Jersey territory became a major commuter carrier. A lot of money was spent on grade crossing elimination, track elevation and new stations before electrification in 1930 to Dover, Gladstone and Montclair. Electrification was viewed as the best way to squeeze more trains onto existing tracks.

Erie Lackawanna handled about half of the New Jersey/New York commuter volume with over 35,000 daily passengers riding over 200 trains. Much of the ex-DL&W work was done with equipment that was already over thirty years old at the time of the merger. Ex-Erie diesel routes used World War I-vintage coaches. Erie Lackawanna’s brief life saw both the end of Hudson River ferry service (1967) and long distance passenger service (1970). It also saw the rise of government subsidy for commuter service and the introduction of new equipment with this help. During this period, Erie Lackawanna also ran a commuter service in the Cleveland area.

The Lackawanna cutoff was built in 1911 as part of William H. Trusdale’s improvement program. This 28-mile cutoff between Slateford and Port Morris bypassed some 40 miles of slow, curved, hilly track. After the formation of CONRAIL, Scranton’s future in railroading appeared bleak. However, the D&H struck a deal to take over the former Lackawanna main line to Binghamton plus Taylor Yard on the Bloomsburg Branch. The downtown property also saw a rebirth as the old station was transformed into a 150-room hotel. Finally, Scranton was fortunate to have Steamtown relocate there.

At East Binghamton, the remains of a coal tower and a roundhouse are still there. The yard is now used by the D&H. Binghamton passenger terminal (DL&W) remains as restored offices. Before the merger, the Erie Limited and the Lackawanna Limited met side-by-side only at Binghamton. The Erie’s terminal has long since been wrecked. Binghamton was a major interchange point with the D&H. It was also the junction with the Syracuse and Utica branches. Branchline trains arrived and departed from platforms at the end of the station.

Buffalo-bound trains follow the old Erie main west from Binghamton. The DL&W line is a dead-end spur, as it has been since the 1960 consolidation. In 1869, the Lackawanna built its own line into Binghamton to avoid using the Erie from Great Bend. The road became a New York-Buffalo trunk line in 1882 when it leased the New York, Lackawanna & Western between Binghamton and Buffalo.

Leaving the main at Binghamton, the Utica branch also included a line to Richfield Springs. Around 1870, the Greene Railroad and the Utica, Chenango & Susquehanna Valley Railroad were built. In 1882, this line was leased to the DL&W.

The Syracuse branch went its own way at Chenango Forks and continued to Oswego. Lackawanna had acquired the Syracuse & Binghamton Railroad as an outlet for its anthracite coal. It continued as a prosperous line until declared redundant with the creation of CONRAIL. The S&B had been organized in 1851 and was leased to the DL&W in 1870. Also leased about the same time was the Oswego & Syracuse.

Expansion kept pace with the economic growth of the area. Many areas were double tracked. The 1920’s saw seven or eight daily freights in each direction plus five passenger runs. North of Syracuse, the line passed in front of the New York State Fair Grounds. Before 1938, this led to a huge shuttle business each year. Another big business was hauling limestone for Solvay Process. By the merger, three round trip freights ran to Binghamton. This dropped to two by 1970. Coal trains ran to Oswego until 1963.

Cortland had the largest station between Binghamton and Syracuse. An 18-mile branch to Cincinnatus connected here. Like many other branches, it was abandoned before the Erie Lackawanna merger. Hills near Jamesville required helper locomotives for southbound traffic. Trains for Solvay ran uphill empty and downhill loaded. In Syracuse, both the Lackawanna and the New York Central ran in the middle of city streets. DL&W tracks were elevated in 1940 and a new station was built. Passenger service to Oswego went bus in 1949. Syracuse passenger service lasted until 1958 at which time the station became a bus terminal.

CONRAIL utilizes the north end of the Syracuse branch from Fulton to Oswego for winter month oil shipments to the Niagara-Mohawk power plant. It is named the Baldwinsville Secondary.

Another branch that never made it to the merger was Owego to Ithaca. There was even a genuine switchback on this branch.

Continuing west on the Lackawanna, stations at Apalachin and Nichols still stand but no tracks are nearby. Bath to Wayland became part of the Bath & Hammondsport. There is a 14-mile hiking trail west of Wayland. No more trains climb Dansville hill. The Groveland yard is all grown over. Groveland to Greigsville became part of the Genesee & Wyoming. The Dansville & Mount Morris also runs into Groveland.

Bison Yard in Buffalo was completed in 1963 under joint ownership with the Nickel Plate. In 1971, Erie Lackawanna and Norfolk & Western formed the Buffalo Terminal Division. Before CONRAIL, almost 100 trains per day from six railroads used its facilities. Interchange connections were made with seven others. It was the main connection between EL and Lehigh Valley lines to the east and C&O and N&W lines to the west. Buffalo Terminal lines crossed one another at numerous points and transfer runs with other lines had a choice of routes. Interchanges with Canadian National added an international flavor.

In its heyday, Bison dispatched as many as 4000 cars per day. Hump crews shoved cars through the retarders on a round-the-clock basis. As many as 80 engines per day were fueled, sanded and cleaned.

Bison Yard is gone; it is now an industrial park. The Lackawanna station in Buffalo has been demolished but the trainshed is utilized by the local light rail facility. Buffalo, in general, was decimated by the CONRAIL consolidation.

**********

A “Big Hook” that was once Erie’s

Conrail No. 45210 was an Industrial Brownhoist 250T Wreck Derrick. It was built in 1955 as Erie Railway No. 03302. It rests serviceable at the Railroad Museum of Pennsylvania.

**********

REFERENCE

Erie Lackawanna in the Joe Korner

Early history of the Erie Railroad

New Jersey Railroads Timetable Archive

THE UNIVERSITY OF AKRON. Erie Lackawanna Historical Society Collection.

List of New York Railroads

List of Pennsylvania Railroads

List of Ohio Railroads

List of Indiana Railroads

Special section on Erie-Lackawanna Railroad

Surviving Erie-Lackawanna locomotives

Walt Fles’s ERIE LACKAWANNA Home Page

Erie Lackawanna Railroad and Predecessors

A great e-book!

**********

Former Erie Railroad chairman and railroad reformer Robert R. Young was born February 14, 1897. Chairman of the Board of Chesapeake & Ohio, Erie, Missouri Pacific, Nickel Plate, Pere Marquette, Wheeling & Lake Erie and finally New York Central, he is perhaps best known for his advertising campaign: “A hog can cross the country without changing trains but you can’t”

State Line Interlocking

In its heyday, State Line was one of the most complex interlockings in the United States. It was on the Indiana-Illinois border at the gateway to Chicago.

**********

Erie Lackawanna Railroad

c1962 System Map

Master Mechanic Territories

Studies of possible affiliation between

Norfolk & Western Railway and Erie-Lackawanna Railroad

Erie Lackawanna Railroad

June 9, 1968 Public Timetable

Erie Lackawanna Railroad

Erie Railroad Track Charts

*********

All about EL’s duplicate lines

Graham Line and Main Line

In the early 1980’s, New York State had money to improve one line but not both. They needed to provide more commuter parking and space wasn’t easily available in the towns. There was also the issue of grade crossings in Middletown (about 12!). The freights would not have been welcome on the grades along the ‘Old Main’, and there were then a significant number of them (both freights and grades), while there were only about four daily round trips (in peak hours only) to Port Jervis and no weekend commuter service. It looked like an obvious call to NYS – put the money into the Graham Line, including three new stations, and abandon the Main Line except for a stub at Harriman to reach a freight customer and one to reach the Middletown & New Jersey.

Boonton/Bergen

Greenwood Lake once had a branch that was abandoned, the lines formerly crossed each other at some point, and the “main line” never was the main line of either Erie or Lackawanna, but was given that name when it was swapped after the merger.

Once upon a time, the DLW Boonton Line left the Morristown Line at West End (near the Tonnelle Ave traffic circle under the east end of the Pulaski Skyway). It went northwest toward Paterson, then west to Denville. The Erie Greenwood Lake Line went west from Jersey City through Bloomfield, north through Montclair to a point just south of NJ 3 in Great Notch, northwest through Wayne to Wanaque and once continued to iron mines in Ringwood and to Greenwood Lake itself.

The Erie also had a branch from the Greenwood Lake line in the Harrison area that skirted Newark and then ran north to Paterson, crossing the Boonton line in Clifton. The Erie’s Main Line ran through Rutherford and Passaic on the way to Paterson.

The part of the DLW Boonton Line from West End to Clifton was connected with the Erie line from Newark to Paterson as a replacement for the Erie Main Line, which was abandoned through Passaic, though stubs continued to operate for many years. This became the new EL Main Line.

The part of the DLW Boonton Line from Wayne to Denville was attached to the Greenwood Lake Line just north of Mountain View station and became the new EL Boonton Line. It required a new connecting track off the old Boonton Line near Croxton yard. EL attempted to run freight on this line, but quit running through trains after several derailments left boxcars in the neighbors’ backyards in the small hours of the morning. Possible origin of the phrase ‘not in my backyard’???

The part of the DLW Boonton Line between Wayne and Totowa was kept in service for freight only, and remains today. The part between Totowa and Paterson was sold to NJ (the EL needed the money desperately) and is now under I-80; NJ offered to build a single track alongside the highway at no cost to EL to avoid severing the line but the Cleveland-based EL management declined to its later regret. The section from Paterson to Clifton was also sold to NJ and is now under NJ 19 between Paterson and the Garden State Parkway. Commuter service between Wanaque and Mountain View held on for a few years as a connecting shuttle, with a few through trains, but is also gone.

The Bergen County Line required a short double-track connection in the Secaucus area to connect with the old Boonton Line in the meadows; this connection was removed during construction of the new Secaucus Transfer station. The junction of the Main and Bergen County Lines was the site of a head-on collision which killed both engineers and a passenger; probable cause was fatigue of one engineer and his train ran a red signal into the interlock.

Northern Branch

The Northern Branch suffered the worst: its trains had to execute a back-up move in the meadows to get between the old Erie route and the DLW for Hoboken; that added about 15 minutes to the ride. Commuters quickly deserted to bus lines that were much quicker and also less expensive.

**********

New York & Greenwood Lake Railroad

Picture at top: New York & Greenwood Lake Railroad crosses the Passaic River.

**********

**********

Erie Lackawanna Commuting

The Erie-Lackawanna operated a major suburban service to the New York suburbs in New Jersey. The four routes plus three branches radiate from north to west from Hoboken where there is a connection with PATH rapid transit trains into New York. The NJ&NY line, formerly New Jersey & New York Railroad, travels 30.6 miles to Spring Valley. The New York Division Main Line, along with the Bergen County branch, extend 30.5 miles to Suffern. There is additional service to Port Jervis which is 87 miles from Hoboken. The 48-mile Greenwood Lake-Boonton line goes through Dover to Net Cong. The last line extends 40.5 miles to Dover. There are two branches (Montclair and Gladstone).

In 1970, Erie-Lackawanna commuter volume was 35,000 daily passengers on 210 trains. They ran 98% on-time. EL came into being in 1960 when the Erie and the Delaware, Lackawanna & Western merged. It amounted to the weak banding together to survive. Passenger terminal operations had previously been consolidated at Hoboken. Other operating efficiencies were realized by abandoning and realigning some tracks. Part of the Boonton line was abandoned when a new connection was made with the Greenwood Lake line at Mountain View. Service was abandoned on the Northern Branch (Erie line to Nyack), Newark Branch and Caldwell Branch. Sunday service was lost.

In the mid-1920’s, the Delaware, Lackawanna & Western’s Morris & Essex Division was out of capacity. This New Jersey steam railroad could not squeeze any more traffic onto its tracks or any more tracks onto its roadbed in the New York metropolitan area. The officials decided to electrify the railroad because electric trains, with their higher rate of acceleration, would provide faster service and so handle the increased volume of traffic. Westbound steam trains took 34 minutes to reach Montclair while electrics could cover the distance in 27 minutes. Accordingly, a project was begun in 1928 to electrify the road from Hoboken to Morristown and Dover (the Morris & Essex line) as well as the branches to Montclair and Gladstone which diverge at Roseville Avenue and Summit, respectively.

While other area electrifications were either 600-volt D.C. or 11,000-volt A.C., DL&W went for 3,000-volt D.C. overhead catenary similar to the Milwaukee Road. 70 miles of road (160 miles of track) were electrified. Originally, it was planned to extend the electrification as far west as Scranton, Pennsylvania, and to have heavy duty motors haul long freight trains across the Poconos. Pullman built 140 motor cars which were semipermanently coupled with converted steam-hauled coaches built between 1912 and 1925. This olive-drab commuter equipment served Hudson, Morris, Essex, Union and Somerset counties for over half a century. Most of the cars that started service when the line was electrified were still running at the end. General Electric, as the long-time advocate of D.C. rail traction, was chosen as the car equipment supplier. Each car had four 230 h.p. motors. Because they were rated at 1500 volts, two motors were permanently connected in series. Maximum speed on level track was 67 miles per hour after accelerating at 1 1/2 miles per second. The seats were of stiff rattan and cooling was by ceiling fans. These M-U cars were known as Edison coaches because Thomas Edison dedicated them.

The Gladstone branch, formerly the Passaic and Delaware, is still referred to as the P&D. This scenic, single track 22-mile line, whose catenary is supported on brackets attached to wooden poles; resembled an interurban. Train operation is unusual and fascinating. Off-peak trains were coupled/uncoupled at Summit. Rush hour trains ran to Hoboken. Trains running in opposite directions had scheduled meets.

The railroad operated four “membership” cars. These were for the commuter who had “arrived” economically. They were parlor cars built between 1912 and 1917 with carpeted floors, wicker arm chairs, and ice-activated air conditioning.

Other routes were less important as far as traffic was concerned and were never electrified. There was absolutely no electrification on the former Erie Railroad. These operated to Suffern, Spring Valley and Port Jervis, NY and to Dover and Netcong NJ. Limited modernization on these lines took place after World War II and steam surrendered to diesel by 1953. No attempt was made to replace the vintage rolling stock. In 1970, first-generation diesels were pulling World War I coaches of two types: ex-DL&W “Boonton” cars; and ex-Erie “Stillwell” coaches (remember the arch windows!). EL continued to use the equipment from Erie and DL&W. MU’s, RDC’s and diesel-hauled equipment all served well during Erie-Lackawanna’s 16-year existence. Almost 200 coaches were required to maintain service.

At Hoboken on the Hudson River is an 18-track stub-end terminal where all the commuter lines terminate. Long-haul passengers don’t use it anymore, nor do the ferries that used to run to 23rd Street, Christopher Street and Barclay Street in Manhattan. Instead 25,000 commuters pass through it twice a day in order to use the Hudson “tubes” (really PATH – Port Authority Trans Hudson) (formerly Hudson & Manhattan). 198 electric and 115 diesel trains operate from Hoboken.

Hoboken, formerly solid blue-collar, has been invaded by Yuppies who have rehabbed townhouses and given the city a new tone. It is colorful and full of history. It also is the hometown of Frank Sinatra.

Hoboken’s terminal has a waiting room rich in ornamentation and is finished in Louis XIV style. It measures 10,000 square feet and is 55 feet high. One side is ticket windows. Two other walls are occupied by small shops and a bank of telephones. Two flights of stairs lead to the upper level where commuters used to catch the ferries. The upper level is mostly vacant now. A highlight of the waiting room is the Tiffany stained glass ceiling. When opened in 1907, it was considered the world’s greatest waterfront terminal. The track canopies were originally panels of glass. They were eventually replaced by other materials which required less maintenance. Many panels are missing and commuters sometimes find themselves in the open. A formal entrance from Hoboken streets is not used by many commuters as the PATH-train connection is all inside. Unused is a boarding area where motorists drove their cars onto the waiting ferries. In 1981, $4.8 million was spent in an initial restoration and other funds have followed. A new ferry service now operates not from the terminal but instead from a barge in the river.

Hoboken is now home to NJ Transit’s business car – an open-end observation car. There is also a lot of work equipment in the yard to the side of the train sheds.

When the ferries were discontinued in 1967, only 8,000 daily riders used them. As well as the subway tunnels, their business was killed by the Holland Tunnel, Lincoln Tunnel, George Washington Bridge and the Pennsylvania Railroad tunnels. The 1990’s saw ferries returning!

Hoboken had been DL&W-only until 1957. That year the Erie mostly moved out of its Pavonia Street Station in Jersey City. Their Northern Division to Nyack was left (for a while until passenger service dropped). Three years later, DL&W and Erie merged into the Erie-Lackawanna. This made Hoboken the third-largest passenger station in the country (after Penn Station and Grand Central).

The electric trains to Dover share the Hoboken terminal with the locomotive-hauled trains. After passing a big yard, they operate through the Bergen Hill tunnel, beyond which many non-electrics turn off for a run through the Jersey Meadows. The electrics run through an affluent area with beautiful scenery, interesting station buildings, and continuous curves and grades.

With government help, several improvements were made: 1967 saw 105 push-pull cars from Pullman and 23 diesels from GE come on the property. In 1969, NJDOT acquired 26 1939 Budd streamliners from Sante Fe. Also the E-L cars and E-8’s used in intercity service became commuter when long-haul passenger traffic was killed.

The need for power compatible with the rest of the Northeast Corridor killed the old electrification. Already bankrupt, EL gave up to CONRAIL in 1976. The western portion (no commuter service) was abandoned or cut back as old Penn Central routes saw a concentration of traffic. Now this is a NJTransit operation in New Jersey and Metro-North in NY State.

**********

Lackawanna Cutoff

Of all the commuters in America, residents of a small town in eastern Pennsylvania spend the most time behind the wheel, according to the Census Bureau.

Commuters living in the area of East Stroudsburg, a town near the New Jersey border, averaged 40.6 minutes from home to work or vice versa, according to the 2008 Census report released Monday.

That’s a lot longer than the nationwide average of 25.5 minutes.

Roger DeLarco, president of East Stroudsburg council, said that’s because many of the locals travel to jobs in the New York City area, more than 60 miles east as the crow flies. He said that 10,000 people live in his town, but three times that number commute to New York from the greater area of East Stroudsburg.

In a reversal of the trend it appears that some of the abandoned Lackawanna Cutoff is finally being rehabilitated!

I’m not holding my breath for the full restoration to Scranton, PA, but this is a good start.

The Unofficial Web Page for the Lackawanna Cutoff Passenger Rail Project

Click on picture above to find out about the Penn Jersey Rail Coalition

Another Lackawanna Cutoff Page

The Great Lackawanna Cutoff – Then & Now

Railroad.net discussion of the Lackawanna Cutoff

Lackawanna Cutoff from the Wiki

Also known as “New Jersey Cutoff”

Six Rail Station Sites

From the Pocono Record

Delaware Water Gap

From the National Park Service

Old and New Stations on the Lackawanna Cutoff

| DL&W Milepost | Town/City | Station / Facility | Comment |

| 45.7 | Roxbury Township | Port Morris Junction | NJT’s Port Morris rail yard. NJT Morristown Line to Hoboken Terminal and Penn Station. |

| 53.0 | Andover | Andover | Proposed NJT station. None previously. |

| 57.6 | Green Township | Greendell | Station closed 1934. Potential future maintenance-of-way facility. |

| 60.7 | Frelinghuysen Township | Johnsonburg | Station closed 1940. |

| 64.8 | Blairstown Township | Blairstown | Proposed station. |

| 71.6 | Hainesburg (Knowlton Township) | Paulinskill Viaduct | No station. |

| 73 | Stateline (NJ/PA) | Delaware River Viaduct | No station. |

| 74.3 | Slateford | Slateford Junction | Junction with Old Road – No station |

| 77.2 | Delaware Water Gap | Delaware Water Gap | Proposed Park & Ride station. Previous park & ride) was vacated in 1967. |

| 81.6 | East Stroudsburg | East Stroudsburg | Proposed station. |

| 86.8 | Analomink | Analomink | Proposed station. |

| 100.3 | Mount Pocono | Pocono Mountain | Proposed station. |

| 107.6 | Tobyhanna | Tobyhanna | Proposed station. Station closed 1958. |

| 133.1 | Scranton | Scranton | Proposed station. Former station: other uses. |

**********

Lackawanna Cutoff: Getting Back on Track

On June 29, 2006, John Cichowski wrote an article in the Bergen Record.

He talked about this being the 50th anniversary of the day that an American president got out of his sick bed to sign the Federal Highway Act, the law that eventually unified the continental United States via 46,000 miles of seamless, high-speed interstate highways unencumbered by intersections, traffic signals or rail crossings.

This achievement had been Dwight Eisenhower’s dream since 1919, a time when railroads were the only means of long-distance travel. But by 1956, competition from cars, trucks and planes was bankrupting the dominant lines. Ike’s Autobahn, as some called Eisenhower’s interstates, finished off the mighty railroads like the Erie-Lackawanna.

To see the glory of this faded era, drive Route 80 to the Delaware Water Gap and and see the seven graceful arches of the 115-foot-tall Paulins Kill Viaduct. Once the world’s tallest concrete rail bridge, this majestic span carried trains over the Pequest River into the rolling hills of Pennsylvania. Paulins Kill was a link in a series of bridges, tunnels and embankments called the Lackawanna Cutoff, which carried freight and passenger trains from the Delaware River to Morris County, where it linked to rail lines now run by NJ Transit. This 28-mile stretch was abandoned two decades after Route 80 was built. The track was torn up in 1984. Weeds now cover much of Paulins Kill’s majesty.

But if Ike were to drive this part of his autobahn at rush hour today, he might go back to bed.

Pennsylvania traffic to the employment hubs of Morristown, Wayne and Paramus has clogged Route 80 for a decade. Nearly 20,000 Monroe County, Pa., residents commute to New Jersey and Manhattan, a figure likely to double by 2020. With the population of Warren and Sussex counties predicted to rise 40 percent by 2020, gridlock is a certainty.

As it is, the U.S. Department of Transportation gives this stretch its worst congestion rating.

So, a half-century after Ike, Congress and Interstate 80 consigned the cutoff to oblivion, New Jersey and Pennsylvania want NJ Transit to revive it for passenger service to ease highway congestion. Both states bought the right-of-way from Conrail for $21 million, and a restoration proposal will soon be submitted to the Federal Transit Administration. Construction costs will exceed $350 million, mostly for track and rail stations.

On the surface, this plan should excite visionaries, commuters and taxpayers. Since the route is set through farmland, the cost is relatively low. No neighborhoods face wrecking balls. In a way, it would supplement Eisenhower’s unification dream with an efficient alternative. The Pennsylvania Northeast Regional Rail Authority states that rail right-of-way is 80 to 100 feet wide compared to interstate right-of-way that can be 500 feet wide. If approved, the cutoff’s main line tracks could carry as many passengers as a 20-lane highway. For the first time since 1979, someone could board a diesel in Scranton and alight in Manhattan or one of dozens of stops on the combined, 130-mile Pennsylvania and New Jersey lines.

Critics in New Jersey, however, question the cutoff’s value. The biggest objection lies in the fact that the rail line, like the highway, will produce additional suburban sprawl, especially in the Highlands, which supplies drinking water for millions. But legislation is already in place to limit development. The other objection rests on the fact that the great majority of the 6,700 commuters who will benefit from the cutoff each day live in Pennsylvania, not New Jersey. They question why funds are not being directed at projects that would benefit more New Jersey residents.

One plan would link Hawthorne and Paterson to Hackensack. Another would collect passengers in Monmouth, Ocean and Middlesex counties, the fastest-growing region in New Jersey and one of its slowest-moving. The Northern Branch line would connect Tenafly, Ridgefield and the terminus of the Hudson-Bergen Light Rail line in North Bergen for twice the cost of the cutoff.

All have merit. The competition for federal money is fierce. Can a proposal featuring little towns like Scranton and Morristown compete with the urban titans of mass transit?

The benefits for such a small expenditure are hardly small. They’re immediate. They’re long-term. And they would ease the travel of workers in two states. Anybody who drives Route 80 at rush hour can appreciate their enormity.

**********

Pennsylvania Northeast Regional Rail Authority

In February, 2006, Lackawanna County, Pennsylvania, and Monroe County, Pennsylvania, agreed to merge their rail authorities.

Their conclusion was that the operation of a railroad is not a one county venture. It takes a regional approach as trackage begins and ends outside individual county boundaries. It is necessary to have ample resources to operate a railroad in a very competitive environment and conversely, to obtain the funding necessary to operate a railroad from the State and Federal governments.

The Lackawanna Railroad Authority, established in 1985 has over $16 million dollars in assets and operates more than 66 miles of track in Lackawanna, Wayne and Monroe Counties. The Monroe County Rail Authority was created in 1980, and controls over $12 million in assets with trackage totaling 29 miles.

**********

Now New York State wants to get into it too! Binghamton to Scranton!!!

WITH BINGHAMTON AREA IN NEED OF SPEEDY, RELIABLE TRANSPORTATION TO NEW YORK CITY, SCHUMER URGES AMTRAK TO STUDY BINGHAMTON-SCRANTON TRAIN LINE TO CONNECT SOUTHERN TIER TO NEW YORK CITY

Binghamton Area Currently Lacks Air and Train Routes to New York City Metropolitan Region

With Scranton-Hoboken Line Moving Forward, Expanding Rail Service from Scranton to Binghamton Would Provide Vital Link to New York City and Profoundly Impact Economic Development in the Region

Today, Schumer Calls on NYSDOT and Amtrak to Conduct Feasibility Study for Passenger Rail Service Along the Interstate 81 Rail Corridor

Today, U.S. Senator Charles E. Schumer urged the New York State Department of Transportation (NYSDOT) to get Amtrak to conduct a feasibility study for a passenger rail service to connect Binghamton, New York, and Scranton, Pennsylvania along the Interstate 81 rail corridor. The project would provide a direct link to New York City for Binghamton area residents, affording them an important new transportation option, as well as boosting economic development. The Binghamton area currently lacks direct air and train service to New York City.

“Establishing a rail link between Binghamton and New York City is a win-win that holds tremendous potential to boost economic development in the Southern Tier,” said Schumer. “Besides giving Binghamton residents vital new transportation option, it would also allow New York City businesses to more effectively tap into the regions first-class labor pool for new development opportunities. A feasibility study is the essential first step to make this idea a reality.”

In a letter to NYSDOT Commissioner Astrid Glynn and Amtrak CEO Alexander Kummant, Schumer today urged the company to conduct a feasibility study that analyzes the costs and benefits of passenger service and documents commuter patterns. The scope of the study is intended to compliment the Binghamton Based Intercity Rail Passenger Study submitted to New York State Department of Transportation in 2002. Once the state requests this study, Amtrak can move forward with the project using existing funds already budgeted for this purpose.

Schumer stressed that an existing joint Pennsylvania-New Jersey effort to return commuter based service between Scranton, Pennsylvania, and Hoboken, New Jersey, known as the New Jersey-Pennsylvania Lackawanna Cutoff Rail Restoration, holds the potential to create a rail link from Binghamton to New York City, via Scranton and Hoboken. The Lackawanna Cutoff Project will connect with existing New Jersey Transit Lines leading into New York City. The Binghamton-Scranton line would hook up to the Lackawanna Cutoff Project once it is completed for access to New York City, complementing this project by providing even more access for riders.

This passenger rail expansion would provide countless benefits to Binghamton residents who would take advantage of this new service to ultimately gain access to New York City by way of Scranton and Hoboken. Additionally, with this new service, more business and leisure travelers from New York City would be able to access the many assets—from academic facilities to businesses and cultural opportunities—that Binghamton has to offer, and tap into the local economy for new economic development opportunities.

“We all firmly believe that rail service connecting the Greater Binghamton area to the New York City area would have a positive impact on our community,” said Broome County Executive Barbara J. Fiala. “At this stage of the game, however, it is important that we get data to back up our beliefs and therefore I want to thank Senator Schumer for encouraging Amtrak and New York State Department of Transportation to conduct this feasibility study. It will provide an important benchmark in our efforts to develop passenger train service to New York City.”

A rail line connecting Binghamton and New York City is especially crucial in the wake of the Delta Airlines decision in July of this year to terminate its air service at the Greater Binghamton Airport, despite ridership spiking 43% over the past year. This decision axed the direct Binghamton-JFK flight and has left potential New York City commuters with no way to easily access the Southern Tier.

**********

Binghamton Train Service???

There is no question whatever that there has been a migration of middle income families in the $60K-$100K income range desiring to fulfil the “American Dream” who relocated from renting in “the Boroughs’ to home ownership in Eastern Pennsylvania. These two New York Times articles from 2004 detail the sacrifices the families have made, the long commute by bus just being one of such, relocating in the hope of finding a better life.

Possibly NJT service will come to a restored DL&W route using the abandoned yet intact Lackawanna cutoff, but all should be mindful that there cannot be any feasible NY-Binghamton service to be operated by ANY agency until that comes to pass.

There are the political realities to consider for the ‘first hurdle”: NJT, as a State agency, is “in business’ to transport New Jersey residents to their livelihood so that they can pay State income taxes and Local real estate taxes. Therefore to make a substantial investment in rail facilities to transport Pennsylvania residents to their livelihood in New York “might not go over too well’ with an NJ taxpayer, or two.

OK let’s now extend this line of thought to the “what if’ that there was restored passenger service along the DL&W, regardless of agency, to the Eastern PA market The Times notes? Let us consider the environment into which an intercity service would be placed.

First, the only agency that holds authority, and the necessary “right of access”, is Amtrak. At present (and likely continuing indefinitely) there is a “moratorium” on new Federally funded routes. That means “Local Bucks” will have to be in play. Pennsylvania is willing to fund intercity trains so long as they will take passengers to attractions within Pennsylvania. They are happy to support a Harrisburg resident who desires to shop and listen to the pipe organ at Wanamakers; not so happy about supporting one who desires to see the Rockettes and shop at Macy’s in New York. New Jersey appears only willing to fund passenger trains operated by THEIR agency, or NJT.

**********

Original purpose of the Delaware, Lackawanna & Western was to bring Scranton to the world.

In the process, it became a major trunkline. Over the years, the DL&W was known by many nicknames: to the employees, it was “DL”; advertising campaigns referred to it as “The Route of Phoebe Snow” or “Road of Anthracite”; and critics sometimes called it the “Delay, Linger & Wait”. In fact it sometimes claimed to have the best engineered right-of-way in the world.

It all began with the Liggett’s Gap Rail Road incorporated in 1849. It ran from the Pennsylvania coalfields at Scranton to Owego via Great Bend with a connection with the Erie. Coal was sold in cities at a good price but coalfields were cheap because there was no transportation. Coal was always important to the DL&W. As early as 1854, the road owned 2500 acres of coal-bearing land. In the 1860’s and 1870’s, 80 percent of the tonnage was coal. As late as 1925 coal tonnage was still more than 50%. In 1870, several coal companies owned by Lackawanna directors were merged into the railroad. This amounted to about 25,000 acres of anthracite-bearing land. Became Lackawanna & Western

The Ithaca & Owego Rail Road was chartered in 1828 and completed in 1834. It had a difficult line leaving Ithaca because of the grade. Originally it used inclined planes then an underpowered engine. A failure, it was rebuilt by George Scranton and became part of the Lackawanna in 1855.

The Delaware and Cobb’s Gap Railroad Company was incorporated in 1849 by some local businessmen. It ran across the Poconos from Scranton to the Delaware Water Gap. It consolidated with the Lackawanna & Western in 1853 to form the Delaware, Lackawanna & Western. Later connecting with the Warren Railroad in 1856, it became part of the Lackawanna in 1857.

The Morris & Essex Railroad was how the Lackawanna finally reached New York harbor. Early on, access was via the Central Railroad of New Jersey. The M&E had been incorporated in 1835 and originally ran from Morristown, NJ to Newark. Because of the panic of 1837, it took another 11 years to reach Dover. In 1854, it extended from Newark to Hoboken but became overextended financially. DL&W president Samuel Sloan made a deal to lease the line in 1868. Part of the deal was a new, easier route through New Jersey, known as the Boonton Line.

The Syracuse, Binghamton & New York Railroad Company was built between 1851 and 1854 and purchased by the Lackawanna in 1869. Also purchased at this time was the Oswego & Syracuse Railroad. To bridge an eleven-mile gap from a Hoboken to Great Lakes route, the Valley Railroad Company was constructed. A branch ran from Cortland to Cincinnatus.

The Utica, Chenango & Susquehanna Valley Railroad was organized in 1866 and came under the Lackawanna in 1870. Inclusion of the Greene Railroad Company linked up this road with the Syracuse route at Chenango Forks. As well as providing an important link, it also put the Lackawanna in the resort business. The branch to Richfield Springs was on Canadarago Lake and tourist trains now ran from Hoboken. This line was a big dairy carrier and solid milk trains ran until the late 1940’s.

Chenango Forks, a small rural village 12 miles from Binghamton, is situated at the junction of the Tionghnioga River and the Chenango River. It served as the juncture of the Syracuse and Utica branches. There was CTC control to/from Binghamton with timetable and train order control over the rest of the branches.

Coal loading at Oswego was “big time” years ago. Trains up to 100 cars pulled in daily. The New York Central also used the DL&W facility. Competition came from the nearby D&H/O&W dock. Also close by were the Pennsylvania at Sodus Point, Lehigh at Fair Haven and B&O at Rochester. The decline in lake shipping plus the decline in coal use put the dock out of business.

The Lackawanna & Bloomsburg Railroad Company was the last important branch added to the system. Chartered in 1852, it was acquired in 1873. It followed the Susquehanna River from Scranton to Northumberland and served the coal-rich Wyoming Valley.

The poor decision to go with a six-foot track guage was corrected in 1876. In the early 1880’s, the road built a double-track line from Binghamton to Buffalo. Also in this period, several smaller lines in New Jersey were leased or otherwise acquired. Jay Gould tried unsuccessfully to take over in this period. As a result, the DL&W built to Buffalo by 1882.

Much of the story of the Lackawanna is the story of its presidents:

Samuel Sloan served 31 years and worked every day he was president. He treated the property like a personal domain. Originally with the Hudson River Railroad, he left because he didn’t work well with Cornelius Vanderbilt.

William Truesdale was president beginning in 1899. He undertook a complete modernization of the road. Bridges were rebuilt and grades were reduced. He rebuilt the Hoboken Terminal and took over ferry service in 1903. He rebuilt the main line in New Jersey (after which known as the “Cut-Off). With the exception of some grade reductions, the main line had remained unchanged since the 1860’s. It consisted of the former Morris & Essex from Hoboken to Washington then the former Warren Railroad to the Delaware River. It followed the line of least resistance. To cut the distance, several alternatives were considered. One involving grades was dismissed as this would require helper engines. The new line ran from the Delaware Water Gap at Slateford, PA to Lake Hopatcong in New Jersey. The new line was opened in 1911.

West of Scranton he built many concrete viaducts including one across the Tunkhannock Creek at Nicholson. This viaduct carries trains 240 feet above the valley over a 2375 foot span between the ridges. It is a poured concrete structure and was built between 1912 and 1915. There are ten exposed arches but the structure contains an additional arch buried in the fill at each end as an abutment anchorage. Another large viaduct was built at Martin’s Creek about eight miles away. Because it is only 1600 feet long and 150 feet above the creed, it never became as famous.

Truesdale bought heavier locomotives and got out of the coal business. He retired in 1925.

A Texan named John Marcus Davis led the railroad through the depression. He electrified suburban commuter service around 1930. William White took over in 1941. Perry Showmaker took over presidency when White went to the D&H in 1951. Hurricane Diane tore up railroad in 1955. The main line was broken and traffic had to make long detours.

The most famous passenger train was the “Phoebe Snow”. It ran from 1949 to 1967 and was named for a pre-World War I figure who advertised the cleanliness of the Lackawanna’s hard coal. Throughout the 1950’s it ran with clean equipment in good repair. The train had distinctive tavern-lounge-observation cars with a classic drum sign. The Lackawanna was able to handle high peak density service. Typical of this requirement were holiday weekends at the Pocono resorts. Some weekends would see the “Phoebe Snow” running in three sections with over thirty cars. Power was FP-3’s, E-8’s and FM Trainmasters. Heavy days would even see MU trailers from New York commuter service being used.

1960 merger with Erie ended the DL&W as a separate entity.

**********

Erie Lackawanna Newburgh Branch

**********

No station at Greycourt Anywhere

***********

A New Hudson Bridge, Revived Beacon Line, HYPERLOOP and More

The Maybrook Line was a line of the New York, New Haven and Hartford Railroad which connected with its Waterbury Branch in Derby, Connecticut, and its Maybrook Yard in Maybrook, New York, where it interchanged with other carriers.

If one looks at the most popular Pages on our WebSite, over half directly reference the Maybrook Line. Lot’s of folks have an interest in it. The “Maybrook Line” was important to New England before the advent of Penn Central and before the Poughkeepsie Bridge burned. This piece of the railroad carried freight from Maybrook Yard, across the Poughkeepsie Bridge to Hopewell Junction where it joined a line from Beacon. The railroad then went to Brewster, then Danbury, and finally to Cedar Hill Yard in New Haven.

WHY and How To Fix The “MAYBROOK LINE”?

Container port/intermodal facility/rail bridge

The construction of a railroad bridge between New Hamburg and Marlboro is likely the least expensive place to build a Hudson River crossing between Manhattan and Albany. The stone for ramps, sand and gravel for concrete and a steel beam assembly and storage area would be right on sight. All materials and equipment could be transported by barge or boat. The bridge itself would have only four or five piers (the most costly part to build) since the Hudson River is about the same width as it is in Poughkeepsie.

The Hudson River component connects Dutchess, Ulster and Orange counties to the world economy (finished goods, spare parts, components parts, raw materials, food stuffs) and the railroad and interstate road components connect these NY counties to the rest of North America (US, Mexico, Canada).

With the container port/intermodal facility/rail bridge, the flow in and out of raw materials, spare parts, partially finished goods, foodstuffs and components will allow for new industries and businesses to locate near this facility and add to the tax base of these three NY counties: Dutchess, Ulster and Orange counties.

Although the Dutchess County Airport is a tiny regional airport with a 5,000 foot runway, it has some big potential. The airport land extends a mile Northeast of the present runway end at New Hackensack Road and borders on the former New Haven Maybrook Line/Dutchess Rail Trail. As the NY Air National Guard gets crowded out by international air traffic at Stewart International Airport their operation could be moved over to Dutchess Airport without disrupting the lives of the guard members and their families through forced relocation.

Beacon itself is exploding with “developer” activity, and it needs a trolley or light rail for the city only to transform back into a pedestrian oriented city.

Other activities include: Solidization of rail links in Connecticut to handle increased traffic; a possible HYPERLINK for improved service along the Beacon Line and in/out of New York City

Now you are going to ask. What does the New York City Metropolitan Transportation Authority have to do with the “BEACON LINE”? IT OWNS IT! Must realize that NYCMTA is a “regional” organization. With all that went on with Penn-Central and CONRAIL somebody had to own it!

So what would a “revised” rail line look like?

To begin with, the line from Maybrook to the Hudson River is gone. Railroads that previously entered Maybrook can reach the Hudson River and head up the old West Shore to the proposed bridge at New Hamburg. But the old Poughkeepsie Bridge is no longer in service, as well as the tracks to Hopewell Junction. At Marlboro, trains would take the old New York Central Hudson Division to Beacon, New York. Yes, with both Metro North and Amtrak using the Hudson Line, it may require an additional track.

From Beacon trains would travel the Beacon Line over the Housatonic Railroad to Derby-Shelton, Connecticut. Trains would go to Cedar Hill Yard. Some traffic may go to Long Island. With traffic revitalized, other trains will even go to Waterbury!

***********

A great, great WebSite about HUDSON VALLEY RAILROADS

No, it is not ours! It is very comprehensive and professional.

http://www.hudsonrivervalley.org/library/pdfs/Railroads.pdf

It is written by professionals, not railfans. Lots of really neat stories about the old railroads. Lots of great links too!

All about the Walkway Over The Hudson (old bridge from Maybrook to Beacon)

All about Metro-North Railroad

From their biblioraphy:

“New York Central Railroad and New York State Railroads.” GOURMET MOIST / Kingly Heirs. Web. 13 Oct. 2010. . This website talks about the different railroads that eventually merged to form the New York Central Railroad. It also discusses where the railroads runs to and from.”

Since 2010, it has become a part of our WebSite:

https://penneyandkc.wordpress.com/new-york-state-railroads-and-ny-central-railroad/

***********

You must be logged in to post a comment.